Patriots for Truth – by Guy Cihi

The factual events underpinning this version of American history are drawn from conventional history books, expository articles, and personal diaries. References are provided below. The difference between this telling and the history taught in American public schools is that the intentions of the actors described herein are more logical to the facts.

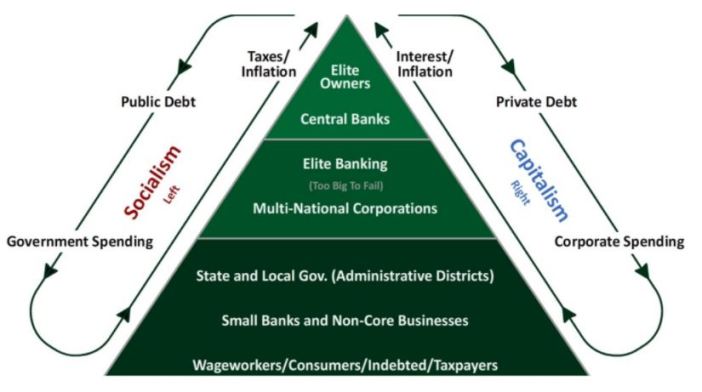

The facts suggest that it was the Crown itself that organized and financed Washington’s Continental Army. Without the Crown’s support there would be no US Federal Government and no Rothschild Central Bank in America today. Corrupt Federal Governments and Central Banks are how the Crown controls and enslaves its colonies. This article outlines how the Crown executed its plans to give the American Colonies the false impression of independence whilst maintaining control through a newly established, corrupt Federal Government, a Constitution that agents of the Crown drafted, and soon enough, a foreign-owned Central Bank.

The Actual War

In 1778 France and England declared war. This war is called the Bourbon War in Britain and the Anglo-French War in France. The beleaguered and bankrupt King Louis the XVI went all in on this war. Sadly it was a war that he would soon lose. Louis XVI would be the last king of France and he would pay for his defeat with his head. Americans are still paying for hs defeat thanks to fiat debt enslavement. Louie’s failure ushers in the French Revolution; another British masterpiece of skullduggery, and gives birth to the French Republic under Napoleon.

British King George III was only just beginning to apply the Crown formula of divide and conquer among England’s commodity-rich colonies scattered about the world. The Crown’s enduring global domination can be directly attributed first and foremost to its central banking scheme; secondly to its Hegelian political deceptions, and thirdly to its advanced weaponry obtained through intellectual property theft.

Key Players Set the Trap

In 1778, American “Ambassador” Benjamin Franklin was living high with Marie Antionette and Louis in the palace at Versailles. In return for King George’s many indulgences and gifts, Franklin negotiated disadvantageous terms for the Colonies in every treaty he negotiated. In 1778, Franklin’s mission at Versailles was to convince King Louis XVI to participate in the American revolution. Franklin’s stay at Versailles was bankrolled by agents of King George III. Living descendants of first-hand witnesses attest to Franklin’s clandestine meetings with Crown agents at Montreal’s Hôtel Pierre du Calvet. This author has stayed in the same room Franklin used for his secret meetings.

The photo above shows hundreds of skeletons unearthed in Franklin’s London townhouse basement. These tiny tortured skeletons were found during the 1998 renovations of Franklin’s London townhome; the home provided to Franklin by the Crown. Was Franklin a practicing Satanist in addition to being a loyal servant of the Crown?

After George Washington’s fake 1776 “victory” at Trenton, Franklin was finally able to get a deal with Louis XVI whereby France would extend the Colonists credits with which to “pay” for French mercenary soldiers, war material, and the naval harassment of British ships. In return, the Colonists were to keep Britain bogged down while France assembled a naval fleet for the invasion of the Crown’s super-rich sugar colony, Jamaica. Remember, all wars are commodity wars.

Louis XVI was being systematically deceived into believing that his navy and marines could wrest the rich sugar colony from the Crown. If France’s Jamaican attack had been successful, it would have diverted about 20 percent of King George’s free cash flow directly into Louis’s near-empty coffers. Louis took the bait and the British trap was set.

Propping up Washington and His Continental Army

By 1777 Britain was well along in implementing its plans to “lose” the unprofitable American Colonies whilst at the same time deceive Louis XVI into believing his warships and naval tactics were superior to those of the British navy. This was not an easy thing to accomplish because Washington’s Army was even more tattered than the rotting barnacle-encrusted hulls of the French warships.

The only real problem the British ever faced in the Colonies were the highly effective independent militias that were kicking British and Hessian asses all up and down the coastline. These guerrilla attacks changed the minimal cash flow coming in from the American Colonies into annual losses. Had Washington’s Continental Army fallen apart as expected in January of 1777, the independent militias would have gained more power and the British plans to exit without loss of control would likely have been set back several decades.

It became essential for the Crown to step in to maintain the impression of a viable Continental American army so the Crown would have a single corrupt counterparty to negotiate peace terms with. In the winter of 1776-77, the only way to accomplish that was for the Crown to feed, clothe, and pay the ragtag Continental Army as quickly as possible. This explains why thousands of new leather boots, woolen garments, tons of food, booze, cash money, and gunpowder were all stockpiled and left practically unguarded for the Americans to take in Trenton, New Jersey on December 26, 1776.

Not a single American died in the fake Battle of Trenton. Most of the 22 Hessian casualties were officers because, well, dead men tell no tales. Autopsies may likely reveal the Hessian officers were shot in the back by pissed-off Hessian mercenaries who must have quickly realized just why their sentries and guard posts had been recalled the night before, and why the report of an approaching rebel force was ignored by their commander.

After feeding, paying, and clothing his ragged Continental Army with the loot that British General Howe had so kindly stockpiled in Trenton, Washington set about thwarting French Marquis de Lafayette’s efforts to attack the British at their weakest points. Instead of actually fighting the British, Washington only begged the French king for more credits with which to “pay” for more materials and naval harassment of British ships. Washington also kept himself busy working on fake plans to not attack New York City. It seems that General Washington never attacked anywhere that he wasn’t invited to attack. The few successful Colonial attacks, such as the Battle of Saratoga, were led by militiamen under the command of local Patriot heroes – the kind of men Washington was put in place to undermine.

Faking Not One But Two Critical Defeats

By 1780, the British plans were in the final stage and Lord Cornwallis was ready to pretend to lose the ground war to Lafayette and the French mercenaries. Oh right, George Washington was there too. The place chosen for this was Yorktown, a desolate location that is practically good for nothing even to this day. Despite the narcissism of Americans, this British false flag was entirely orchestrated for the benefit of King Louis XVI. The purpose of the fake defeat at Yorktown was to suck Louis further into the British trap – a trap that would ultimately cost Louis and his young wife Marie their heads.

The fake British defeat at Yorktown gave Louis XVI the impression that his French army and navy had beaten the British army and navy at the Battles of Yorktown and the Chesapeake. In fact, the two battles were complete farces. Cornwallis purposefully positioned his fort on the wrong side of the river to make it easy for the French mercenaries to drop mortar rounds on top of it. The British warships sent from New York to engage the French blockade purposefully avoided sinking any French ships and then, inexplicably “ran away” back to New York.

The French warships were loitering in the Chesapeake, just off Yorktown, with their meters running-up charges the Colonists would soon regret having incurred. The French ships were there to blockade Lord Cornwallis from receiving British resupply from the sea. On the morning of September 5, 1781, the French ships were caught completely unaware and at anchor by multiple British warships that had come down from New York. Instead of sinking the French warships as they lay defenseless at anchor, British Commander Thomas Graves ordered his warships back out to open sea, giving French Admiral Compte de Grasse four hours to onboard his sailors; weigh anchors, and set out to engage the, oh so very kind British.

The Battle of the Chesapeake was short and indecisive. After a couple of hours, the British “escaped” to the north. The French did not pursue. Why? Because their old ships were 20 percent slower than the newer British ships. At Yorktown, it was made to appear as if the French had defeated the British both on land and at sea. No historian can explain these things logically and so a wide variety of unsatisfying excuses are given instead. How were the vastly superior British army and navy both defeated at Yorktown? The logical answer is that they were not defeated. The battles were pantomimes and part of a trap designed to entice King Louis XVI further along in his plan to invade Jamaica to take the Crown’s super-rich sugar plantation away from King George III.

The Set Up is Complete

Following the false “victories” at Yorktown, French Admiral Compte de Grasse sailed his rotting French fleet back to the Caribbean to prepare for the coming invasion of Jamaica. Meanwhile, the Crown moved ahead with its plans to establish a controlled Continental Congress that would ratify a Constitution that would enable a Rothschild central bank. Crown loyalists including Hamilton, Adams, and others were paid to prepare competing (Hegelian dialectic) drafts of an American Constitution. The final document would give the impression of being hard fought for through heated debate but in truth the final Constitution enabled the Crown’s plans.

Fake Battles – Fake Treaties

Regardless of what has been reported about the peace treaties, the Crown gave away nothing, and it did not surrender after Yorktown. None of the several treaties that were signed ever required the Crown to abandon any of its rights, claims, and properties within the 13 Colonies. What actually happened was Crown loyalists Franklin and Lee negotiated America’s conditional surrender to the Crown. The American’s conditional surrender is made clear in the first Treaty of Paris, a document that simply altered the form of the Crown’s dominion over the 13 Colonies. The only thing the American Colonists actually “won” were some off-season whaling concessions along the coast of Greenland. For his bungling performance, George Washington was rewarded with King George’s personal commendation and support for becoming America’s first President.

Instead of multiple policed territories, the newly united states became a federally managed, semi-autonomous tax farm. The Treaty of Paris transferred the Crown’s costs to police the colonies to the colonists, and within just a few years the Crown’s investment in the colonies was returned to marginal profitability. Remember, the only valuable commodity coming out of America at that time was tobacco. The cotton gin wasn’t invented until 1794 and despite efforts to find it, there was almost no gold or silver.

The Real Battle Royale

Seven months after Admiral Compte de Grasse’s “victory” in the Battle of the Chesapeake, the French and British fleets met in the Caribbean in what is known as the great Battle of the Saintes. Compte de Grasse suffered a humiliating defeat. This time it was British Admiral Rodney who literally sailed circles around the slower French warships, pounding them with cannon fire from all directions. The absolute French defeat at the Saintes marked the end of Louis XVI’s reign, and the end of the French monarchy.

In surrendering to the British; along with many more of his assets, Louis XVI was required to transfer his Colonial receivables to King George. In a subsequent British-American treaty, the Colonies were forced to accept the transfer of their war debts from Louis to King George’s Crown Bank of England. With that transfer, Americans became Crown debt slaves in perpetuity.

Deception and Treachery

It was Commander Graves’ deceptive tactics at the Battle of the Chesapeake in September 1781 that tricked the French into believing their barnacle-encrusted old oaken warships had a chance of prevailing against the much newer and faster British copper-clad warships. That deception may well be the Crown’s greatest success in mind control, possibly right up there with the Crown virus of 2020, and the WTC “terrorist attack” on September 11, 2001.

Sadly for the once-again outplayed Americans, their surrender to the Crown initiated formation of a corrupt central government, a Rothschild central bank, and an insurmountable mountain of fiat national debt. It would be unfair to describe Washington, Franklin, Hamilton, Adams, and so many others as actual traitors, because there was no actual America at the time to be traitorous to. The concept of American national patriotism was another British mind game created later during the War of 1812 and specifically for the purpose of further increasing the national fiat debt.

Were There Were No Patriot Heroes?

There were a few brave and true American patriots alive at the end of the 1700s. Men like Jefferson, Stephen and Burr. These men gave us the Bill of Rights, the only American legal document that actually does protect Americans from total domination by the Crown. Until such time that Americans wake up and turn against the U.S. corporation acting in their name, the Crown will continue to rob and pillage America’s wealth.

.

References

- Allison, David K; Ferreiro, Larrie D, eds. (2018). The American Revolution: A World War. Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 9781588346599.

- Ayling, Stanley Edward (1972). George the Third. London: Collins.

- Barros, Carolyn A.; Smith, Johanna M. (2000). Life-writings by British Women, 1660–1815: An Anthology. UPNE. ISBN 978-1-55553-432-5. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- Bemis, Samuel Flagg (2012). The Diplomacy of the American Revolution. Read Books Ltd. ISBN 9781447485155.

- Berenger, Jean (1997). A History of the Habsburg Empire 1700–1918. New York: Longman. ISBN 0-582-09007-5.

- Black, Jeremy (2006). George III America’s Last King. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300117325.

- Blanning, Timothy (1996). The French Revolutionary Wars. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-340-56911-5.

- Boromé, Joseph (January 1969). “Dominica during French Occupation, 1778–1784”. The English Historical Review. JSTOR 562321.

- Chartrand, René (2006). Gibraltar 1779–83: The Great Siege. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-977-6. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- Colomb, Philip (1895). Naval Warfare, its Ruling Principles and Practice Historically Treated. London: W. H. Allen. OCLC 2863262.

- Dull, Jonathan R (2009). The Age of the Ship of the Line: The British & French Navies, 1650–1815. Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 9781473811669.

- Grainger, John D (2005). The Battle of Yorktown, 1781: A Reassessment. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-8438-3137-2.

- Greene, Jack P; Pole, J.R, eds. (2008). A Companion to the American Revolution. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470756447.

- Falkner, James (2009), Fire Over The Rock: The Great Siege of Gibraltar 1779–1783, Pen and Sword, ISBN 9781473814226

- France, Kingdom of; United States of America (1788). “Treaty of Alliance”. The Avalon Project, Yale Law School. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- Glascock, Melvin Bruce (1969). “New Spain and the War for America, 1779-1783”. LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses, 1590. Louisiana State University. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- Hagan, Kenneth J (16 October 2009). “The birth of American naval strategy”. In Hagan, Kenneth J.; McMaster, Michael T; Stoker, Donald (eds.). Strategy in the American War of Independence: A Global Approach. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-21039-8.

- Jackson, Kenneth T; Dunbar, David S. (2005). Empire City: New York Through the Centuries. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-2311-0909-3.

- Hardman, John (2016). The Life of Louis XVI. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300220421.

- Harvey, Robert (2004). A Few Bloody Noses: The American Revolutionary War. Robinson. ISBN 9781841199528.

- Ketchum, Richard M (1997). Saratoga: Turning Point of America’s Revolutionary War. New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 9780805061239. OCLC 41397623. (Paperback ISBN 0-8050-6123-1)

- Lavery, Brian (2009). Empire of the seas: how the navy forged the modern world. Conway. ISBN 9781844861095.

- Kochin, Michael S; Taylor, Michael (2020). An Independent Empire: Diplomacy & War in the Making of the United States. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472054404.

- Mahan, Alfred T (1957). The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660–1783. New York: Hill and Wang.

- Mahan, Alfred T (1898). Major Operations of the Royal Navy, 1762–1783: Being Chapter XXXI in The Royal Navy. A History. Boston: Little, Brown. OCLC 46778589.

- Marley, David F (1998). Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the New World, 1492 to the Present. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598841008. OCLC 166373121.

- Mirza, Rocky M (2007). The Rise and Fall of the American Empire: A Re-Interpretation of History, Economics and Philosophy: 1492–2006. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4251-1383-4. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- Morris, Richard B (1983) [1965]. The Peacemakers: The Great Powers and American Independence.

- Morris, Richard Brandon, ed. (1975). John Jay: The winning of the peace: unpublished papers, 1780-1784 Volume 2. Harper & Row. ISBN 9780060130480.

- O’Shaughnessy, Andrew (2013). The Men Who Lost America: British Command during the Revolutionary War and the Preservation of the Empire. Oneworld Publications. ISBN 9781780742465.

- Page, Anthony (2014). Britain and the Seventy Years War, 1744-1815: Enlightenment, Revolution and Empire. Macmillan International Higher Education. ISBN 9781137474438.

- Pratt, Julius William (1971). A History of United States Foreign Policy. Prentice-Hall. ISBN 9780133923162.

- Reeve, John (16 October 2009). “British naval strategy: war on a global scale”. In Hagan, Kenneth J; McMaster, Michael T; Stoker, Donald (eds.). Strategy in the American War of Independence: A Global Approach. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-21039-8.

- Renaut, Francis P. (1922). Le Pacte de famille et l’Amérique: La politique coloniale franco-espagnole de 1760 à 1792. Paris.

- Richmond, Herbert W. (1931). The Navy in India 1763–1783. London: Ernest Benn.

- Rodger, Nicholas A.M. (2005). The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain, 1649–1815. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Rogoziński, Jan (1999). A Brief History of the Caribbean: From the Arawak and the Carib to the Present. Facts On File. ISBN 9780816038114.

- Schiff, Stacy (2005). A Great Improvisation: Franklin, France, and the Birth of America. Thorndike Press. ISBN 978-0-7862-7832-9. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- Scott, Hamish M. (1990). British Foreign Policy in the Age of the American Revolution. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820195-3.

- Simms, Brendan (2009). Three Victories and a Defeat: The Rise and Fall of the First British Empire, 1714-1783. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 978-0-1402-8984-8.

- Stockley, Andrew (1 January 2001). Britain and France at the Birth of America: The European Powers and the Peace Negotiations of 1782–1783. University of Exeter Press. ISBN 978-0-85989-615-3. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- Stone, Bailey (2014). The Anatomy of Revolution Revisited: A Comparative Analysis of England, France, and Russia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107045729.

- Syrett, David (30 June 2007). The Rodney papers: selections from the correspondence of Admiral Lord Rodney. Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-6007-1. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- Syrett, David (1998). The Royal Navy in European Waters During the American Revolutionary War. Univ of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-238-7.

- Regan, Geoffrey (2012). Great Naval Blunders. Andre Deutsch. ISBN 978-0233003504.

- Tombs, Isabelle; Tombs, Robert (2010). That Sweet Enemy: The British and the French from the Sun King to the Present. Random House. ISBN 9781446426234.

- Trew, Peter (2006). Rodney and the Breaking of the Line. Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 9781844151431.

- Tuchman, Barbara (1988). The First Salute: A View of the American Revolution. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0-394-55333-0.

On Franklin, he was a member of the Hellfire Club, and yes, they discovered those bones on his basement and then I knew he was likely to be a satanist. And it is also that one cannot get allodial title to land could be because this article states truth that wouldn’t be stated in any school whatsoever…public school, private school, home school materials will never reveal these facts. But I’ve seen videos stating you can get allodial title in Texas…thing is, so much land today in Texas is in subdivisions called PROPERTY Owners Associations or HOME Owners Associations; you can tax property, not land, right?