All US states take pinpricks of blood from newborns to test for diseases. New Jersey stores them for decades and may allow them to be used in police investigations.

When Hannah Lovaglio’s children were born, she didn’t think twice about the newborn health screening they received in the hospital. The routine test uses a few drops of blood from a heel prick to test for dozens of potentially fatal or disabling genetic diseases.

“I assumed that this was for my child’s best interest and for the best interest of public health,” says Lovaglio, a pastor in New Jersey. What she didn’t know was that after testing was completed, the leftover blood would be stored by the state for 23 years and could be used for purposes beyond medical testing. In a court case that became public last year, New Jersey police allegedly used a baby’s blood sample to investigate its father for a crime.

Lovaglio has joined a federal class action against the New Jersey Department of Health and its Division of Family Health Services, which oversees the state’s newborn testing program. She and the other plaintiffs are suing the state over its storage practices. They argue that parents aren’t told how long the samples are kept, or that their child’s blood could be used in other ways.

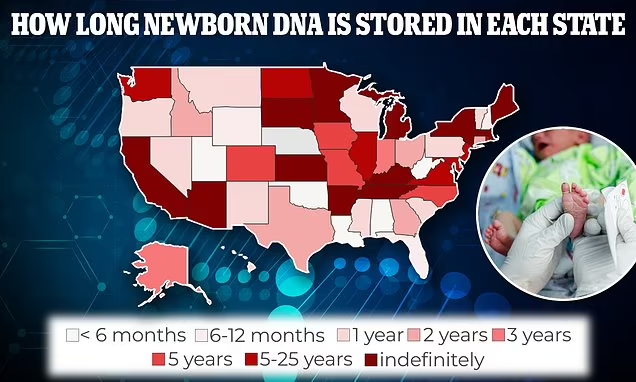

In the United States, all newborns get a heel prick test, but states set their own policies on how long the blood samples are stored. Virginia retains them for just six months if infants have normal results. Other states keep them for years or decades. “New Jersey is among the worst of the worst,” says Brian Morris, an attorney with the Virginia-based Institute for Justice, which filed the lawsuit along with several parents.

“As we see it, what New Jersey can do with this blood and DNA is limited by the state’s own imagination,” Morris says. And with rapid advances in genetic technology, he says there’s no telling what new capabilities the state will have a few decades from now.

In the US, these screening tests are mandatory and cover a minimum of 35 disorders, although New Jersey and others have opted to add more. New Jersey requires that every baby be tested for 61 disorders within 48 hours of birth. While state law doesn’t require the unused blood to be destroyed, it doesn’t explicitly authorize the state to keep it for a certain period of time either. But the state’s records retention schedule indicates that the samples are kept for 23 years.

The Institute for Justice, a libertarian nonprofit, and the parents behind the lawsuit claim there’s no reason for the state to keep samples that long. “The New Jersey Department of Health has unilaterally determined that it can keep and store the unused blood from every baby born in New Jersey,” the lawsuit alleges.

In the lawsuit, filed on November 2, the plaintiffs argue that New Jersey’s practices violate their children’s Fourth Amendment rights against unreasonable searches and seizures. The suit asks the court to bar the Department of Health from keeping blood samples after screening is completed, unless it obtains informed consent from parents to keep the blood for specific, disclosed purposes.

Nancy Kearney, a spokesperson for the New Jersey Department of Health, which includes the Division of Family Health Services, told WIRED via email that the agency does not comment on pending litigation.

When Lovaglio learned earlier this year that New Jersey police departments have purportedly used newborn blood samples to help investigate crimes, she was unsettled. Last year, the New Jersey Office of the Public Defender discovered that state police had allegedly obtained a newborn blood sample from the Department of Health and performed a DNA analysis that allowed investigators to link the baby’s father to a crime that occurred in the 1990s. “The more I sat with it, the more I realized that there was information that belonged to my children that I had no control over. It was nagging,” Lovaglio says.

She says parents should be informed of the state’s storage policy and be able to opt in to how their child’s blood sample can be used. For instance, some states may use newborn blood samples for medical research, but require parental consent to do so. “If there was something that the state told me they could do with my child’s blood samples that would benefit the greater good, I would likely opt into that,” Lovaglio says. “But I want the chance to opt in.”